|

Introduction by Jim Liddane

On Thursday December 21st, 1967 - an actor from Limerick, Ireland, entered Sound Recorders Studio in Hollywood, Califoria, accompanied by songwriter Jimmy Webb. That day, they recorded Webb's latest composition "MacArthur Park", a song which had been already turned down by The Association.

Six months later, on June 22nd 1968, "MacArthur Park" topped the American charts, turning Limerick's Richard Harris into an unlikely rock star, and in the process, making him the first Irish recording act to ever reach the top of the charts in the United States.

Back in "Official Ireland" however, Richard's achievement went more or less un-noticed. Although the record also topped the charts in Australia and Canada, and made #4 in the UK - it barely scraped into Ireland's Top 10, dropping off the charts after a run of just eight weeks.

In Richard's home city, nothing much changed either, although here, "MacArthur Park" did top the local sales charts, staying at #1 for an incredible eight weeks, holding off even The Beatles ("All You Need is Love"), Scott McKenzie's "San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)" and Engelbert Humperdinck's mammoth hit "The Last Waltz".

And so, it would be another 25 years (in spite of the best efforts of Tuesday Blue two decades later) before anybody from Limerick would top the American charts again.

But when they did....

Prologue

The early days of The Cranberries were marked by modest beginnings, rapid development, and the emergence of a unique sound that would soon resonate far beyond their native Limerick.

The band’s roots went back to 1989, when brothers Noel and Mike Hogan, on guitar and bass respectively, joined forces with drummer Fergal Lawler and a friend, Niall Quinn who had his own group The Hitchers but who now also served as the new band’s vocalist. They called themselves The Cranberry Saw Us, a play on words that hinted at their quirky, slightly offbeat approach.

The initial incarnation of the group played a handful of local gigs and recorded a short demo, but it quickly became apparent that Niall wasn’t committed to being the full-time frontman. Instead he suggested that the band look for a replacement, and that recommendation led to a pivotal moment in the band’s history. Dolores O’Riordan, a young singer-songwriter from nearby Ballybricken, auditioned for the role. The band was immediately impressed — not only by her haunting voice but also by her melodic sensibility and lyrical depth. Her arrival marked the real beginning of what would eventually become The Cranberries.

With Dolores now on board, the band shortened their name to The Cranberries and began to develop a signature sound that mixed jangly guitar textures with dreamy melodies and emotionally raw lyrics. In 1990, they recorded their first demo tape which included early versions of songs like "Linger" and "Dreams." This demo caught the attention of local music manager Pearse Gilmore, who helped them record a more polished demo, known as "Water Circle", at his studio. Distributed on cassette, "Water Circle" featured four tracks — "Linger," "Sunday," "Chrome Paint," and "A Fast One" and began circulating through industry hands in both Ireland and the UK.

Their demos eventually found their way to the desks of major record labels in London, sparking a bidding war that culminated in The Cranberries signing with Island Records in 1991. The band traveled to the UK to begin recording their debut album, but their initial sessions with producer Stephen Street were shelved due to pressure from the label and disagreements with an alternative producer imposed on them. The early recordings with the outside producer failed to capture the spirit and subtlety of the band’s demos, leading to a temporary loss of momentum.

However, the group eventually reconvened with Stephen Street, who had previously worked with The Smiths and Blur, resuming production under more favorable terms. Street’s sensitive approach and understanding of the band’s style proved to be a perfect fit, allowing the songs to breathe and giving Dolores O’Riordan’s vocals the space they needed to shine. It was during this time that the songs that would make up "Everybody Else Is Doing It, So Why Can’t We?" began to take their final shape.

Before the album’s release in 1993, The Cranberries toured extensively, opening for acts such as Suede and Duran Duran. These performances helped them hone their live sound and build a grassroots following. Though the music press was initially hesitant to embrace them, word of mouth spread quickly - especially after MTV picked up the video for "Linger." The blend of Dolores O’Riordan’s lilting voice, Noel Hogan’s shimmering guitar lines, and an immaculate rhythm section supplied by Fergal Lawler and Mike Hogan that prioritised mood over bombast, provided a refreshing departure from the grunge-dominated charts of the early ’90s.

By now, The Cranberries had already grown from a little-known Limerick band into rising stars of the alternative rock scene. Their early days had been marked by youthful determination, artistic intuition, and a quiet confidence that allowed them to stay true to their identity even as the music industry tried to mold them into something else. The band’s perseverance during those formative years laid the groundwork for the phenomenal global success that was soon to follow.

The Albums

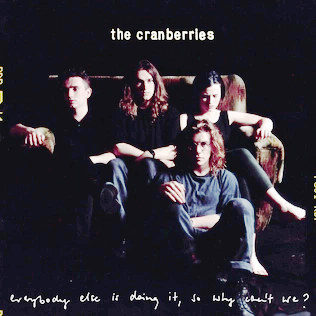

The Cranberries’ debut album "Everybody Else Is Doing It, So Why Can’t We?", released on Island Records on the 1st March 1993, stands as a poignant, dreamlike entry into the musical landscape of the early 1990s — a time when alternative rock was beginning to dominate airwaves, yet few bands approached it with the same delicacy and lyrical introspection that The Cranberries did. This offering was not a bombastic declaration of intent, but rather a graceful unveiling: quiet, assured, and utterly disarming.

The album, which featured twelve tracks, was produced by Stephen Street and recorded at Windmill Lane Studios on Ringsend Road, Dublin, Ireland, and at Surrey Sound Studios on Kensington Road, in Leatherhead, Surrey, UK.

It went on to sell in excess of 8 million copies, going gold in Denmark, Mexico and France, platinum in Australia, Canada and New Zealand, double-platinum in the UK, and five-times platinum in the United States and reaching Númber 1 in Ireland and the UK - a remarkable result for a debut album.

Of the twelve songs, one ("Close To You") was written by Hal David and Burt Bacharach, three ("Waltzing Back", "I Will Always" and "How") were credited to Dolores O'Riordan, while the remaining eight were penned by Dolores and Noel Hogan. In all, two tracks, "Dreams" and "Linger" were released as singles.

From the opening notes of "I Still Do," the album announced itself with a softness and intimacy that was almost subversive for its era. The instrumentation throughout is clean and unassuming, built largely on Noel Hogan’s chiming guitars, Mike Hogan’s subtly melodic bass lines, and Fergal Lawler’s understated drumming. The production by Stephen Street — renowned for his work with The Smiths — allowed the songs to breathe, giving space to the real centerpiece of the album: Dolores O’Riordan’s voice. Her vocals on "Everybody Else" are arresting in their clarity and emotional honesty. Her ability to shift from a gentle murmur to a soaring lament, often within the same line, imbued the lyrics with a confessional quality. This was particularly evident on the album’s two standout singles, "Linger" and "Dreams."

"Linger," a song of betrayal and yearning, was carried by a string arrangement that lent it a timeless elegance, while "Dreams," bursting with optimism and romantic wonder, captured the giddy ache of youthful love. Both songs remain among the most iconic of the decade, not only for their melodic beauty but for the way they seemed to tap directly into universal emotions with astonishing purity.

The rest of the album is similarly textured with longing and vulnerability. "Sunday" and "Pretty" explored themes of confusion, insecurity, and the search for self-worth, while "Waltzing Back" and "Not Sorry" hinted at a more assertive tone beneath the album’s surface gentleness. Even in its more upbeat moments, the album never strayed from its core emotional honesty. There was a quiet courage in Dolores O’Riordan’s writing — her willingness to express doubt, fear, and desire without posturing or artifice was rare in a musical climate often dominated by irony or aggression.

Lyrically, the album was steeped in personal reflection, yet its themes were universally resonant. Much of it was written while the band was still coming of age, and the songs reflect that sense of young adulthood teetering between innocence and experience. The title itself — "Everybody Else Is Doing It, So Why Can’t We?" —encapsulated the band’s outlook: a mix of self-doubt, quiet defiance, and a longing to belong.

Though the album was not an immediate commercial hit, it began to gather momentum thanks to the strength of its singles and the band’s persistent touring. With the support of MTV, radio play, and a growing fanbase, it eventually climbed the charts, particularly in the United States and the United Kingdom. By the end of its run, it had sold millions of copies worldwide, making The Cranberries one of the most successful new acts of the decade.

More than thirty years later, "Everybody Else Is Doing It, So Why Can’t We?" endures not only as a snapshot of early ’90s alternative music but as a deeply human, emotionally intelligent work of art. Its influence can be felt in the wave of introspective indie and dream pop artists that followed, and its songs continue to resonate with listeners across generations. As a debut, it was remarkably assured; as an album, it remains a quietly monumental achievement in emotional storytelling through song.

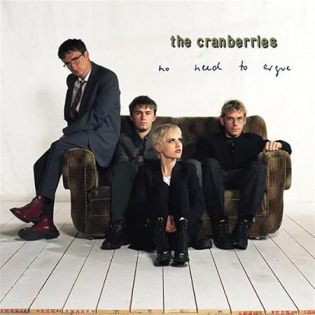

Released on October 3rd, 1994 on Island Records, "No Need to Argue" was The Cranberries’ second studio album, and it confirmed the band’s transition from promising newcomers to one of the defining alternative acts of the decade. Building on the melodic foundations of their debut, "Everybody Else Is Doing It, So Why Can’t We?", the record presented a darker, more forceful tone both musically and lyrically, revealing a group newly confident in its identity. It combined the haunting intimacy of Dolores O’Riordan’s voice with a rawer, more guitar-driven sound that reflected both personal turmoil and broader political unease.

The album, which featured thirteen tracks, was produced by Stephen Street and recorded at The Manor Studios in the village of Shipton-on-Cherwell in Oxfordshire, UK, at the Townhouse in Shepherd's Bush, London, UK, and at the Magic Shop Studios in Lower Manhattan, New York City, USA.

Of the thirteen songs, seven were written by Noel Hogan and Dolores O'Riordan, while six were credited solely to Dolores. Four tracks, "Zombie", "Ode to My Family", "I Can't Be with You" and "Ridiculous Thoughts" were released as singles.

It went on to sell in excess of 17 million copies worldwide, going gold in France and Italy, platinum in Argentina, Austria, Germany, Netherlands, New Zealand, Poland, Sweden and Switzerland, double-platinum in Belgium, triple-platinum in Spain and the UK, five-times platinum in Australia, Denmark and Canada, and seven-times platinum in the United States, and reaching Number 1 in eleven countries.album.

The album opened with “Ode to My Family,” a tender, reflective ballad that set a tone of longing and nostalgia. With its plaintive cello line, gentle strumming, and Dolores's yearning delivery - “Understand what I’ve become / It wasn’t my design” - the song captured the tension between youthful ambition and the ache for simpler roots. It was one of the band’s most affecting works, both understated and emotionally direct.

By contrast, “Zombie,” the album’s most famous track, erupted with anger and despair. Written by Dolores in response to the 1993 bombing in Warrington, England, which killed two young children, the song represented a dramatic stylistic departure. Layered with heavy, distorted guitars and thunderous drums, it carried a grunge-inspired intensity that placed The Cranberries firmly in the mid-’90s alternative rock landscape. Dolores's searing vocal performance - alternating between ethereal verses and an anguished, shouted chorus - channeled both fury and sorrow, transforming the song into an international anthem of protest. Its video, with its stark religious imagery and gold-painted Dolores, became one of the defining visuals of the MTV era.

Elsewhere, "No Need to Argue" explored the fragile spaces between love, loss, and identity. “I Can’t Be With You” combined ringing guitars and a driving rhythm with lyrics of separation and regret, while “Twenty One” and “Daffodil Lament” expanded the band’s emotional range, blending melancholy melody with dynamic shifts and delicate textures. The latter, in particular, was one of teir most ambitious compositions, evolving from soft introspection to a sweeping, cathartic close.

Songs like “Empty” and “Disappointment” revealed the band’s growing sophistication in arrangement and tone. The production, by Stephen Street, balanced clarity and atmosphere - retaining the clean, chiming guitars that had defined the debut, but grounding them with greater depth and weight. His experience with The Smiths and Blur was evident in the mix’s ability to let Dolores's voice cut through the instrumentation without sacrificing the band’s collective cohesion.

Lyrically, Dolores's writing was notably more confessional and direct. She sang of heartbreak and alienation, but also of strength and survival. Her Irish lilt and occasional use of Celtic melodic phrasing lent the songs an unmistakable sense of place, even as the themes were universal. Noel Hogan’s guitar work alternated between bright arpeggios and dense, distorted layers, while Mike Hogan’s bass and Fergal Lawler’s drumming gave the music a rock-steady, understated pulse that anchored its emotional volatility.

The title track, which closed the album, stripped away much of the arrangement leaving just a voice and a spare organ accompaniment. It was an elegiac, almost hymn-like conclusion - a moment of weary reflection after the turmoil of what had come before. Its simplicity underscored the emotional sincerity that ran through the record.

Critically, "No Need to Argue" divided opinion upon release: some found its heavier sound a jarring departure from the debut’s pastoral charm, while others praised it as a bold and necessary evolution. Over time, it has come to be regarded as the band’s artistic peak - a record that fused introspection and outrage, melody and dissonance, with uncommon grace. Commercially, it was a major success, selling over 17 million copies worldwide and cementing The Cranberries’ place among the most influential alternative rock groups of the 1990s.

More than three decades later, the album endures not just for its singles but for its atmosphere - the mixture of vulnerability and defiance that Dolores conveyed so instinctively. "No Need to Argue" captured a band coming into its full power, and an artist whose voice could move from a whisper to a wail and make both feel utterly human.

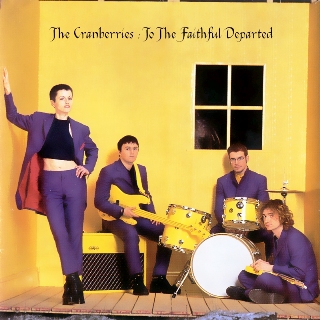

The band’s third album, "To the Faithful Departed", released on the 29th April 1996, marked a striking shift in tone and ambition for The Cranberries. Following the international success of "No Need to Argue", which had established them as one of the defining voices of mid-1990s alternative rock, the group sought to create a record that reflected the turbulence of both the wider world and their own rapidly changing circumstances. The result was an album steeped in grief, anger, and moral confrontation, a raw response to loss and disillusionment that pushed their sound and songwriting into darker, more forceful territory.

Recorded in Dublin's Windmill Lane studios and at the Armoury in Vancouver, Canada, and produced by Bruce Fairbairn, known for his work with acts like Aerosmith and Bon Jovi, the album carried a heavier, more muscular sound than its predecessors. It traded much of the ethereal shimmer and folk-inflected melancholy of the earlier records for distorted guitars, urgent tempos, and a sense of restless agitation. Dolores O’Riordan’s songwriting, always emotionally direct, became more openly political and personal, drawing on global anxieties and intimate bereavement alike. The death of the band’s close associate Denny Cordell who had signed them to their first recording contract and the passing of Dolores O’Riordan’s grandfather Joe O'Riordan, cast a long shadow over the record, lending its title and much of its lyrical content a tone of mourning and reckoning.

It went on to sell in excess of 6 million copies, reaching Number 1 in seven countries.

Of the fifteen songs, eleven were credited to Dolores O'Riordan, while the remaining four were penned by Dolores and Noel Hogan. In all, four tracks, "Salvation" "Free To Decide", "When Your'e Gone" and "Hollywood" were released as singles.

The album opened with “Hollywood”, a song that balanced bright melodic hooks with biting commentary on fame and artifice, as O’Riordan lamented the pressures and illusions of celebrity culture. “Salvation”, one of the album’s standout tracks and its most immediate single, bristled with punk energy and caustic humour, railing against addiction with the shouted refrain “Salvation, salvation, salvation is free.” Its driving rhythm and distorted urgency signalled a band no longer content with wistful introspection; here they confronted the world head-on, with conviction and a hint of menace.

Elsewhere, the tone shifted toward sorrow and reflection. “When You’re Gone” captured Dolores's gift for writing songs of aching simplicity, pairing a lilting melody with lyrics that expressed grief and longing with disarming clarity. “Free to Decide” combined vulnerability and defiance, its chorus a plea for autonomy amid scrutiny and emotional strain. Both tracks stood as reminders that even amid the album’s heavier sonics, The Cranberries’ melodic instincts and emotional resonance remained intact.

The record’s middle section delved further into social commentary and existential unease. “War Child” took aim at the devastation of conflict and the innocence destroyed in its wake, echoing the political consciousness that had defined earlier songs like “Zombie.” “I Just Shot John Lennon” revisited the murder of the Beatle with stark bluntness, its title phrase delivered like a grim news report, more lament than sensationalism. These songs revealed Dolores's increasing willingness to fuse personal feeling with collective outrage, crafting lyrics that read as both journalistic and deeply felt.

Musically, "To the Faithful Departed" was perhaps the band’s most divided statement — ambitious in scope but unsettled in identity. Tracks like “Electric Blue” and “The Rebels” explored the tension between aggression and introspection, while “Cordell” offered one of the album’s most moving tributes, a subdued elegy whose tenderness stood in sharp contrast to the surrounding volatility. The album’s production, at times dense and overdriven, mirrored its emotional intensity; it sought to capture the band’s grief and disquiet not through subtlety, but through cathartic force.

Critically, the album received a mixed reception upon release. Some praised its boldness and thematic weight, noting the band’s evolution from jangling dream-pop to something more muscular and socially conscious. Others found its tone uneven and its production overly heavy, arguing that the immediacy of Dolores's voice was occasionally buried beneath layers of sound. Yet in retrospect, "To the Faithful Departed" stands as one of The Cranberries’ most uncompromising works — a document of transition, mourning, and confrontation, as the band wrestled with fame, mortality, and the world’s unraveling.

While it lacked the commercial consistency of its predecessors, the album’s emotional rawness and lyrical conviction gave it a distinctive power. It revealed a group unafraid to expand beyond the wistful romanticism that had defined them, choosing instead to engage with the chaos of life and the inevitability of loss. In doing so, "To The Faithful Departed" captured a moment of reckoning — both personal and artistic — and reaffirmed The Cranberries’ place as one of the decade’s most passionately expressive bands.

In the years that followed its release, "To the Faithful Departed" underwent a gradual critical reassessment. What had once been seen as an uneven or overly forceful departure from the band’s earlier sound came to be appreciated as an emotionally fearless statement, reflecting the restlessness of its time and the honesty of its creator. Listeners began to recognise the album’s imperfections as part of its truth — a work forged in grief and frustration, yet animated by compassion and conviction. In retrospect, it stands as the most unguarded of The Cranberries’ studio albums, capturing Dolores O'Riordan's voice at its most confrontational and its most human. Its themes of mortality, conscience, and resilience have only grown more resonant with time, marking it as a flawed but profoundly sincere testament to the band’s creative courage.

Released on Island Records on the 19th April 1999, the Cranberries' fourth album "Bury the Hatchet" represented both a renewal and a reckoning for the band, arriving after a period of personal strain and creative hiatus that had followed the intense global success of their earlier records. It was during this period also that Dolores O'Riordan gave birth to her first child, Taylor.

The album carried an air of reconciliation - between fame and normalcy, introspection and expression, melancholy and resilience. Its title alone hinted at closure and reflection, a sense of moving beyond past tensions while acknowledging their scars. Musically and thematically, it found the band returning to a more organic, melodic sound after the darker and more confrontational tone of "To Yhe Faithful Departed", suggesting a deliberate step back toward emotional clarity and a rediscovery of balance.

The album, which featured fourteen tracks, was produced by Benedict Fenner and recorded at The Metalworks Studios in Missisauga in Canada, at Windmill Lane Studios in Dublin, Ireland, at the Chateau de Miraval Studios in Correns, France and at Sarm West Studios in Basing Street, London, UK.

Of the fourteen songs, nine were written by Noel Hogan and Dolores O'Riordan, while five were credited solely to Dolores. Four tracks, "Promises", "Animal Instinct", "Just My Imagination" and "You and Me"

were released as singles.

It went on to sell in excess of three million copies worldwide, reaching Number 1 in seven countries.

The opening track, “Animal Instinct,” immediately reintroduced listeners to Dolores O’Riordan’s unmistakable voice in a gentler but still impassioned setting. Built around chiming guitars and an open, ringing rhythm, the song celebrated maternal devotion and the instinctive strength of protection and love. It stood as one of Dolores's most personal statements, written in the wake of motherhood and shaped by a new awareness of vulnerability and tenderness. That theme of renewal continued in “Just My Imagination,” an effortlessly melodic pop song that recalled the band’s early brightness. Its buoyant arrangement and wistful lyrics conveyed a sense of fragile optimism - a daydream of happiness and simplicity after years shadowed by turmoil.

Elsewhere, "Bury the Hatchet" expanded on the emotional spectrum that had always underpinned The Cranberries’ appeal. “You and Me” floated with luminous delicacy, blending domestic intimacy with universal longing, while “Shattered” and “Saving Grace” explored endurance and emotional repair through a subtler balance of acoustic and electric textures. Yet the record was far from complacent. Songs like “Promises” revealed a lingering edge, combining a jagged guitar riff with Dolores's biting delivery to address the dissolution of love and trust. Its raw energy provided a necessary counterpoint to the album’s gentler moments, demonstrating that reconciliation did not mean forgetting the pain that had preceded it.

The production, handled by Benedict Fenner and the band, emphasized clarity and warmth, favouring layered harmonies, clean guitars, and a rhythmic foundation that felt more grounded than the polished aggression of their mid-90s work. There was a deliberate restraint to the arrangements - space left between instruments, a confidence in simplicity - that allowed the emotional core of each song to emerge unforced. The result was an album that felt intimate without being slight, reflective without surrendering vitality.

Lyrically, "Bury the Hatchet" continued Dolores's exploration of personal identity and moral consciousness but filtered through a calmer, more domestic lens. The social commentary that once erupted in songs like “Zombie” or “Salvation” was replaced by introspection, by songs that confronted inner rather than outer battles. Even in its quieter moments, however, there was an unmistakable emotional intensity, a sense that O’Riordan’s voice - sometimes fragile, sometimes fierce - carried the totality of what the band wanted to express.

By the time the album closed with the tender “Dying in the Sun,” a song of quiet surrender and grace, "Bury the Hatchet" had traced a journey from turbulence toward acceptance. It neither disowned the past nor idealised the future, but instead lingered in the bittersweet middle ground of human experience - the place where The Cranberries’ music had always been most resonant.

In its blend of melodic purity, lyrical sincerity, and understated craftsmanship, the album reaffirmed the band’s identity while revealing a deeper emotional maturity. It stood as a thoughtful re-centering of their artistry, offering both continuity and growth, and reminding listeners that beneath the shifts in tone and fashion, The Cranberries’ true power lay in their unguarded honesty.

Released on MCA Records on the 22nd October 2001, "Wake Up and Smell the Coffee" found The Cranberries at a reflective juncture, both musically and personally. Arriving after the turbulence of the late 1990s, the album felt like a conscious attempt to re-centre themselves, returning to the melodic sensibility and emotional candour that had long defined their sound.

Produced once again by Stephen Street, who had overseen their earliest and most successful work, it carried an air of renewal — not as a reinvention, but as a gentle reclamation of identity. The title itself, half-wry and half-revealing, seemed to acknowledge a period of reawakening after years marked by exhaustion, internal strain, and shifting musical climates.

The album, which featured thirteen tracks, was produced by Stephen Street and recorded at Windmill Studios in Dublin, Ireland.

Of the thirteen songs, five were written by Noel Hogan and Dolores O'Riordan, while eight were credited solely to Dolores. Three tracks, "Analyse", "Time Is Ticking Out", and "This Is the Day" were released as singles.

Musically, the album struck a balance between the lushly layered production of their later 1990s output and the more direct, guitar-driven immediacy of their debut years. The opening track and lead single, “Never Grow Old,” set the tone with its warm acoustic textures and lyrical yearning for simplicity amid the passage of time. “Analyse,” one of the album’s standout tracks, encapsulated this mood perfectly — melodic, urgent, and thoughtful, it combined Dolores O'Riordan's soaring vocals with a crisp, radio-ready arrangement that recalled the band’s mid-90s peak without feeling derivative. Its lyrics, reflecting on perspective and self-awareness, hinted at a matured worldview, less reactive than before but no less emotionally invested.

Elsewhere, "Wake Up and Smell the Coffee" displayed the band’s ability to juxtapose tenderness with introspection. “Time Is Ticking Out” conveyed a subtle ecological anxiety, echoing Dolores's growing concern for environmental and humanitarian issues, while “This Is the Day” and “Every Morning” offered optimism framed through the lens of hard-won experience. There was a pronounced domestic and spiritual undertone throughout the record, informed in part by Dolores's own new chapter as a mother. Songs such as “You and Me” and the title track were suffused with themes of gratitude, renewal, and faith — not in any institutional sense, but as a reaffirmation of emotional clarity and connection.

Though the album did not carry the same raw immediacy or cultural impact as "Everybody Else Is Doing It, So Why Can’t We?" or "No Need to Argue", it possessed a quiet assurance that reflected a band comfortable in its skin. Street’s production lent the songs a luminous sheen, enhancing Dolores's vocal range without overwhelming it, and allowing the interplay between her voice and the band’s melodic instinct to breathe naturally. Noel Hogan’s guitar work, by turns chiming and restrained, anchored the album’s sound, while Mike Hogan and Fergal Lawler provided rhythmic precision that kept the material grounded even at its most ethereal.

Critically, "Wake Up and Smell the Coffee" was received as a solid, if understated, effort — a reaffirmation of The Cranberries’ enduring strengths rather than a bold departure. To some listeners, it felt like a return to form; to others, it represented a moment of consolidation rather than progression. Yet in retrospect, its reflective tone and lyrical maturity stand as a fitting close to the band’s initial chapter. There was a sense of completion running through the album — as if The Cranberries, after years of global attention and personal upheaval, were taking stock of what truly mattered.

Following its release, the band now entered a lengthy hiatus, with O’Riordan and other members exploring solo and side projects. In that context, "Wake Up and Smell the Coffee" reads almost as a farewell letter — not definitive, but quietly conclusive, filled with the introspection of artists who had reached a point of calm after intensity. It reaffirmed their melodic gifts, their empathy, and their ability to translate private emotion into songs of universal resonance. While it may not have sought to redefine their legacy, it gracefully sustained it, closing one era of The Cranberries’ story with warmth, grace, and a lingering sense of gratitude.

The Cranberries reunited in 2009 after a lengthy hiatus, and their return to the studio culminated in "Roses", released on Cooking Vinyl Records on the the 21st February 2012, and an album that felt both reflective and rejuvenated.

Recorded primarily in Canada with long-time producer Stephen Street who had shaped much of their early sound, the record carried an unmistakable sense of homecoming. It revisited the atmospheric textures and melodic sensibilities that first defined the band in the 1990s, yet it did so with a maturity and restraint born of time, loss, and perspective. Rather than attempting to reclaim the urgency of their youth, "Roses" seemed to channel the quiet confidence of artists who had lived, learned, and returned with something more measured to say.

The album, which featured thirteen tracks, was produced by Stephen Street and recorded at

Metalworks Studios in Mississauga, Canada, and Miloco Studios in London.

Of the eleven songs, seven were written by Noel Hogan and Dolores O'Riordan, while four were credited solely to Dolores.

From its opening notes, the album announced a subtler mood than the sharper edges of their late-1990s work. "Tomorrow", with its chiming guitars and surging chorus, exemplified the balance the band struck between introspection and optimism. It offered a melodic immediacy reminiscent of their earlier hits, yet the lyricism was more tempered - hopeful but grounded in realism. Dolores O'Riordan's voice, always the band’s emotional core, sounded both familiar and transformed: still capable of soaring clarity, but touched by a faint weathering that lent new gravity to her phrasing.

Tracks like "Conduct" and "Schizophrenic Playboy" showcased the group’s ability to weave melancholic reflection with rhythmic vitality. "Conduct" in particular stood out for its elegiac tone, its delicate interplay of acoustic and electric textures recalling the dreamlike intimacy of "No Need to Argue". Lyrically, the song dwelt on communication and distance, recurring themes in Dolores's writing, while the instrumentation - gentle percussion, reverberant guitar lines, and an understated string arrangement - gave the piece a sense of suspended emotion. In contrast, "Schizophrenic Playboy" nodded to the more sardonic energy of their mid-career work, its biting commentary wrapped in deceptively buoyant pop-rock sheen.

Elsewhere, "Fire and Soul" and "Raining In My Heart" deepened the album’s emotional palette, exploring vulnerability and renewal with a lyrical simplicity that underscored their sincerity. The arrangements throughout "Roses" were spacious rather than grand, giving Dolores's vocals room to breathe and allowing each song to unfold organically. Noel Hogan’s guitar work was characteristically shimmering and melodic, often colouring the songs rather than driving them, while Mike Hogan’s bass and Fergal Lawler’s drums provided a supple rhythmic foundation that felt looser and more organic than in their previous decade of recordings.

The title track, "Roses", served as a fitting emotional centrepiece, steeped in memory and quiet sorrow. It reflected the album’s broader preoccupation with time and transience - how love and loss entwine, and how beauty persists in the ordinary. Dolores's delivery was hauntingly restrained, capturing the bittersweet essence of the band’s reunion itself: a celebration shadowed by the awareness of everything that had passed.

Critically, "Roses" was received as a welcome return to the Cranberries’ strengths, though without the expectation of innovation that had once accompanied their rise. Rather than attempting to redefine their identity, the band reaffirmed it. The album’s strength lay in its coherence and emotional truthfulness; it sounded like four musicians rediscovering their chemistry and trusting in subtlety over spectacle. For listeners who had grown alongside the band, "Roses" offered not a nostalgic echo of the past but a mature continuation of a shared emotional journey.

In the end, "Roses" stood as a graceful reaffirmation of what made the Cranberries distinctive: the fusion of vulnerability and melodic clarity, of introspection and catharsis. It did not seek to compete with their earlier triumphs but to extend their story with dignity and depth. In its quiet confidence and lyrical tenderness, the album marked a poignant chapter in their evolution - an understated yet resonant testament to the enduring spirit of a band reunited not to reclaim fame, but to rediscover meaning through music.

“Something Else,” released on the 28 April 2017 on BMG Records, stood as a striking reimagining of The Cranberries’ musical legacy, and it arrived at a time when both the band and their audience were inclined to look back with reflection rather than nostalgia.

Recorded with the Irish Chamber Orchestra, the album featured stripped-down, orchestral and acoustic reinterpretations of some of their best-known songs, alongside a small number of new compositions. It was a homecoming in several senses: musically, emotionally, and geographically. In revisiting their catalogue, The Cranberries offered not a mere retrospective, but a renewed conversation with their own past.

The choice of setting — the University of Limerick — was more than symbolic. It was a return to the city that had nurtured their beginnings and defined their sound. The collaboration with the Irish Chamber Orchestra gave familiar songs new depth and grace, replacing the electric textures of their early work with strings, acoustic guitars, and delicate arrangements that highlighted the purity of Dolores O’Riordan’s voice. The result was intimate and organic, evoking the kind of clarity and vulnerability that had always underpinned their strongest material.

Produced by the Cranberries, and recorded in the Irish Chamber Orchestra Building at the University of Limerick, it comprised thirteen songs, eight written by Dolores O'Riordan and Noel Hogan, with five credited to Dolores herself.

The album opened with “Linger,” a song that had come to define their early success and enduring appeal. In its new form, it carried a fragile tenderness, the orchestral backing lending a wistful air that accentuated Dolores’s reflective delivery. “Dreams,” once propelled by youthful exuberance and jangling guitars, took on a more contemplative tone, suggesting that what had begun as an anthem of awakening had evolved into a meditation on memory and time. “Zombie,” their most politically charged song, was rendered in a stark acoustic setting that stripped away the aggression of the original and replaced it with sorrow and gravity. In doing so, the band transformed a protest into a lament, revealing the emotional core beneath the defiance.

Elsewhere, songs like “Ode to My Family,” “When You’re Gone,” and “Ridiculous Thoughts” found renewed life in the softened palette of strings and acoustic textures. “Ode to My Family,” in particular, gained poignancy through its orchestral framing; Dolores’s voice, older and more reflective, carried the ache of experience, making its theme of belonging and gratitude even more resonant. “When You’re Gone” became a quiet elegy, its emotional weight deepened by the passage of time, while “Ridiculous Thoughts” emerged as both introspective and resilient, its new arrangement showcasing the intricate balance between fragility and strength that defined the band’s artistry.

The album however, was not totally retrospective. The inclusion of three new songs—“The Glory,” “Rupture,” and “Why” — reminded listeners that The Cranberries were not merely curators of their own history but still capable of meaningful creation. “The Glory,” with its gentle optimism and soaring melody, suggested peace and acceptance, while “Rupture” explored themes of anxiety and disconnection in a subdued, haunting tone. “Why,” the most striking of the new material, combined emotional directness with a sense of catharsis; its lyrical honesty and musical simplicity served as a testament to Dolores’s ability to articulate both pain and healing in equal measure.

“Something Else” was received not as a greatest-hits collection but as a mature reflection on a body of work that had already become deeply embedded in the emotional landscape of many listeners. The album’s acoustic and orchestral settings drew attention to the enduring strength of the songwriting — the clarity of melody, the lyrical sincerity, and the emotional transparency that had always been The Cranberries’ hallmark. Dolores O’Riordan’s voice, slightly deeper and more seasoned, carried traces of both resilience and vulnerability, lending the performances a sense of authenticity that could only come from time and lived experience.

In hindsight, “Something Else” came to represent a poignant final chapter before tragedy struck. It captured the band at peace with their past, returning to their roots in Limerick and revisiting the songs that had defined them with grace and humility. What emerged was not a farewell but a reaffirmation — a recognition that their music, even when reframed and softened, still spoke with undiminished emotional power. The album’s title, quietly suggestive, proved fitting: it was indeed something else — a delicate bridge between remembrance and renewal, and a testament to the enduring beauty of The Cranberries’ sound and spirit.

“In the End,” released on BMG Records on the 26th April 2019, stood as both a culmination and a farewell for The Cranberries, arriving in the wake of unimaginable loss. Following the sudden death of Dolores O’Riordan in January 2018, her bandmates Noel Hogan, Mike Hogan, and Fergal Lawler faced the deeply emotional task of completing the album using her final vocal recordings. The result was a work steeped in grace and poignancy, bridging the past and present of the group’s distinctive sound while offering a final glimpse of Dolores's unmistakable artistry. Rather than attempting to reinvent their style, the band chose to refine and distill it, creating a record that felt both intimate and reflective, as if aware of its own role as a closing chapter.

The album, which featured eleven tracks, was produced by Stephen Street and recorded at Bunker Studio in South-East London and Kore Studios in Acton, West London, UK.

Of the eleven songs, six were written by Noel Hogan and Dolores O'Riordan, one was penned by Dolores and Canadian record producer Dan Brodbeck, while four were credited solely to Dolores.

From its opening track, “All Over Now,” the album struck a tone of dignified melancholy. The song echoed the rhythmic pulse and layered guitar textures of the band’s early work, yet carried a haunting awareness of time and loss. Dolores's voice, clear and resonant even in its fragility, conveyed a maturity that deepened the emotional weight of the music. Songs like “Lost” and “A Place I Know” embodied the reflective quality of the record, balancing sorrow with moments of serenity and introspection. There was a quiet resilience at the heart of these performances, suggesting not only grief but also acceptance and peace.

“The Pressure,” one of the album’s most vibrant moments, provided a sense of lightness amid the reflective tone. Its driving rhythm and hopeful refrain hinted at renewal, a reminder of The Cranberries’ enduring ability to craft melodies that blend melancholy with uplift. “Wake Me When It’s Over” carried a bittersweet irony in its title, yet its rhythmic insistence and lyrical yearning revealed the vitality that remained in Dolores's creative spirit. Throughout the album, her voice was framed with understated care: the production, handled by long-time collaborator Stephen Street, preserved the natural warmth and clarity of her tone without overstatement.

Musically, “In the End” balanced the dreamlike textures of the band’s early work with the more grounded, melodic sensibility that had defined their later years. Guitars shimmered and swelled, bass lines moved with quiet assurance, and Lawler’s drumming anchored the music with restraint and empathy. The arrangements were uncluttered, allowing the emotional resonance of each song to emerge organically. In many ways, the album felt like a conversation between the band’s past and its present —nostalgic but never frozen in time, mournful but not defeated.

Lyrically, Dolores's final songs touched on themes that, in retrospect, carried an almost prophetic poignancy: healing, release, and the passage of time. The closing title track, “In the End,” served as both a lament and a benediction. Its gentle melody and reflective tone captured the essence of farewell — not just to a career, but to an era of shared emotion between artist and audience. The simplicity of the refrain, delivered with unguarded sincerity, left an impression of quiet transcendence.

As an album, “In the End” achieved something rare: it transformed private grief into collective remembrance. It stood as a testament not only to Dolores's enduring talent but also to the integrity and devotion of her bandmates, who shaped the final recordings into a work of beauty and dignity. While it inevitably bore the shadow of loss, the record’s mood was not one of despair, but of gratitude — for the music, for the memories, and for the voice that had once defined a generation of alternative rock. In bringing her final songs to life, The Cranberries offered one last affirmation of their shared artistry, closing their story with tenderness, honesty, and profound respect.

The Legacy

The Cranberries’ legacy still endures as one of the most distinctive and emotionally resonant in modern popular music. They stood apart from their contemporaries through a sound that was both intimate and anthemic, blending jangling guitar textures, Celtic undertones, and an emotional directness rarely found in mainstream rock at the time. With an unmistakable voice at the centre — a voice that could shift effortlessly from ethereal delicacy to defiant power — the band carved out a space that was uniquely their own, bridging alternative rock, dream pop, and folk traditions with striking sincerity.

Beyond commercial success (more than fifty million albums sold worldwide), the group’s influence can be heard in a wide spectrum of artists who followed. Bands and solo performers from Florence + the Machine to Hozier, from Daughter to Wolf Alice, have cited The Cranberries’ ability to blend vulnerability with strength as a touchstone. Dolores’s voice, with its mix of fragility and fierce conviction, opened the way for a generation of female singers who found power in emotional transparency rather than vocal polish alone. In this respect, The Cranberries not only reflected the emotional climate of their era but helped shape the expressive possibilities of alternative rock itself.

Their Irish identity also played a subtle but important role in their legacy. At a time when Irish popular music was still largely defined by either traditional folk or U2’s stadium-scale rock, The Cranberries brought something more introspective and regionally textured. Their accents were never disguised; Dolores's voice carried the inflections of Limerick as proudly as her lyrics carried themes of home, displacement, and belonging. This authenticity helped them connect deeply with Irish and international audiences alike, reminding listeners that pop music’s emotional truths could be sung in any accent, from any corner of the world.

Today, The Cranberries’ music remains both timeless and unmistakably of its moment. Their songs continue to appear in films, television, and online tributes, reaching new audiences who find in them the same blend of yearning and hope that first captivated listeners three decades ago. They stand not only as one of Ireland’s most successful musical exports but as an enduring symbol of emotional honesty in popular music — a reminder that vulnerability, when expressed with courage and melody, can echo far longer than any passing trend.

The Cranberries’ true legacy lies in that enduring echo: the way their music continues to give voice to the unsaid feelings of ordinary lives. They taught the world that sincerity could be revolutionary, that gentleness could be powerful, and that a single, unguarded voice could still change the emotional landscape of modern rock.

The Cranberries’ impact on Ireland extended well beyond their chart success, touching aspects of national identity, cultural confidence, and local pride. For many Irish people, particularly in the 1990s, the band represented a kind of artistic self-assurance that felt fresh and grounded. At a time when Ireland was still finding its place in a rapidly globalizing world, The Cranberries showed that an Irish group could achieve international acclaim without compromising its authenticity, accent, or emotional tone. Their songs sounded unmistakably Irish — not through overt use of traditional instrumentation, but through phrasing, melody, and emotional inflection. Dolores O’Riordan’s voice carried the timbre and rhythm of Irish speech, and she made no effort to conceal it; that choice alone became a powerful act of representation.

In this way, The Cranberries helped broaden the idea of what Irish music could be. They were neither folk nor stadium rock, neither traditional balladeers nor imitators of American trends. Instead, they crafted a distinctly Irish form of alternative pop, melancholic yet melodic, universal yet intimate. For younger Irish artists coming of age in the 1990s and 2000s, that example was liberating. It proved that one could emerge from a small Irish city, write about personal and local themes, and still find a global audience. Their success subtly shifted the landscape of Irish popular culture, helping to normalize the idea that international recognition was compatible with regional identity.

Their impact on Limerick itself was particularly profound. When The Cranberries first gained international fame, Limerick was often unfairly stereotyped in Irish and British media. The band’s rise in that context carried a quiet sense of civic redemption. Here was a group from a modest background in Limerick’s suburbs who conquered the world through talent, perseverance, and sincerity. For Limerick people, the band's success became a source of pride and belonging — a symbol that creativity could flourish anywhere. Over the years, their music became intertwined with the city’s own narrative of resilience and renewal.

Following Dolores O’Riordan’s death in 2018, the outpouring of grief in Ireland, and especially in Limerick, testified to how deeply the band’s story had been woven into the community’s fabric. The city’s tributes — murals, vigils, and memorial performances — reflected not only admiration for her artistry but affection for her as one of their own. The campaign to name a public walkway along the River Shannon the "Dolores O’Riordan Memorial Walk" and the presence of her mural near King John’s Castle symbolized that deep connection between artist and place. In Limerick, The Cranberries are not only a band to be remembered, but are an enduring part of the city’s identity, ad well as a reminder that international art can grow from deeply local soil.

Economically and symbolically, the band’s global success helped raise Ireland’s profile as a creative nation during the 1990s, alongside U2, Enya, and later The Corrs. But unlike those artists, The Cranberries’ connection to a specific Irish city, rather than a broader national stage, gave their story a more grounded texture. They showed that cultural success did not have to originate from a capital city or from established industry circles. In that sense, their journey became part of the evolving story of regional Ireland’s contribution to the country’s modern identity.

Today, in Limerick, The Cranberries’ influence remains palpable — not only through the arrival of overseas visitors and the hosting of commemorative events, but through a quieter, more enduring legacy: the sense that their success was rooted in sincerity and community rather than celebrity. Young musicians in the city see them as proof that great art can emerge from ordinary places and lived experience. Their sound continues to echo in those local bands and singer-songwriters who prize melody, introspection, and emotional truth.

In the end, The Cranberries’ importance to Ireland and to Limerick lies not only in what they achieved, but in what they represented: the idea that art can give voice to both private feeling and collective identity, that local voices can resonate on a global scale, and that one band’s journey from small-town beginnings to worldwide acclaim can change how a community — and a country — see themselves.

Epilogue

There are voices that define a time, and then there are voices that define a place. For those of us who lived in Limerick, The Cranberries did both. The band carried the ache and pride of a city that was yearning to see itself differently, and it travelled far further than any of us could have imagined. Long before the world came to know her as the singer of "Linger" and "Dreams", Dolores was simply one of our own — a young woman with a shyness that couldn’t hide her spark, walking the same streets we walked, speaking in the same quick rhythm of our city.

When The Cranberries began to break through in the early 1990s, Limerick wasn’t the kind of place people associated with global success. The headlines back then too often leaned toward the grim, and the city’s creativity was something that tended to live quietly, in back rooms and rehearsal spaces. Then came four young musicians — Fergal, Noel, Mike and Dolores — who produced songs that felt at once local and universal. The first time I heard "Dreams", that soaring, unmistakable voice seemed to lift the whole city with it. For once, Limerick wasn’t being spoken about; it was speaking for itself.

Above all, the Cranberries never became distant, never became wrapped in the trappings of fame. They spoke plainly, laughed easily, and carried themselves with a sort of quiet self-assurance. And of course Dolores also had that mix of gentleness and mischief that Limerick people admire, and recognise instantly. Of course you accepted that they now belonged to the world, but you also knew that they would never stop belonging to Limerick.

And the band's music captured that same duality. Songs like "Ode to My Family", "When You’re Gone", and "Linger" spoke to the everyday truths of Irish life — the pull of home, the ache of memory, the endurance of love. Even "Zombie", with its anger and defiance, came from that deeply Irish place of empathy and conscience. There was nothing manufactured about it. The songs felt lived in, like the streets and skies we knew.

When news of Dolores's passing broke, the whole city seemed to exhale in disbelief. The day of her funeral, Limerick fell still. It wasn’t just grief for a famous singer; it was the sadness of losing one of our own — a neighbour, a daughter, a voice that had given shape to something unspoken in all of us.

Now, when you walk near the river and see her image gazing out from King John’s Castle, you are reminded of what the Cranberries gave this city. They showed that something beautiful could grow from ordinary beginnings — that honesty and emotion were strengths, not weaknesses.

For Limerick, The Cranberries weren’t just a band that made it big; they were a mirror that showed us our own potential. They took the sound of a small Irish city and made it universal. And though time moves on, that sound remains part of our landscape — rising over the Shannon, carried on the air, still singing to us.

Whenever "Dreams" comes on the radio, you still pause. For a moment, the years fall away, and you see Noel and Mike and Fergal again — and alongside them, that same sharp, laughing girl who now, will never age.

Copyright Songwriter Magazine, International Songwriters Association & Jim Liddane: All Rights Reserved

The above is just one of the many profiles of leading songwriters, singers, musicians and music industry personnel, published by the International Songwriters Association and "Songwriter Magazine". Please click HERE for more.

The Main Menu

ISA • International Songwriters Association (1967)

internationalsongwriters@gmail.com

The Small Print

This International Songwriters Association 1967 site is a non-profit non-commercial re-creation of portions of the full site originally published by the International Songwriters Association Limited, and will introduce you to the world of songwriting. It will explain music business terms and help you understand the business concepts that you should be familiar with, thus enabling you to ask more pertinent questions when you meet with your accountant/CPA or solicitor/lawyer.

However, although this website includes general information about legal issues and legal developments as well as accounting issues and accounting developments, it is not meant to be a replacement for professional advice. Such materials are for informational purposes only and may not reflect the most current legal/accounting developments.

Every effort has been made to make this site as complete and as accurate as possible, but no warranty or fitness is implied. The information provided is on an "as is" basis and the author(s) and the publisher shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damages arising from the information contained on this site. No steps should be taken without first seeking competent legal and/or accounting advice

Some pictures on this site are library images supplied by (amongst others) the ISA International Songwriters Association (1967), International Songwriters Association Limited, Dreamstime Library Inc, BMI (Broadcast Music Inc), ASCAP (American Society Of Songwriters, Authors and Publishers), PRS (Performing Rights Society), PPS (Professional Photographic Services), RTE (Radio Telefis Eireann) TV3, and various Public Relations organisations. Other pictures have been supplied by the songwriters, performers, or music business executives interviewed or mentioned throughout this website, while certain pictures are commercial stock footage of businesses and office environments generally, rather than specific images of the ISA, its personnel, facilities or members.

In any event, all images are and remain the property of the individual owners unless indicated to the contrary.

Home •

Interviews •

Writing A Song

|