|

Introduction by Jim Liddane

Andrew Lloyd Webber, born on March 22, 1948, in London, England, is one of the most influential and successful composers in musical theatre history. His prolific career spans decades and has left an indelible mark on the world of music and theatre. Coming from a musical family—his father, William Lloyd Webber, was a composer and organist, and his mother, Jean Hermione Johnstone, was a violinist and pianist—Andrew was surrounded by music from a young age.

Andrew showed prodigious talent early, composing his first pieces as a child. He pursued his education at Westminster School and later at the Royal College of Music, briefly attending Magdalen College, Oxford, before deciding to focus entirely on his passion for composing. In his late teens, he met lyricist Tim Rice, forming one of the most celebrated partnerships in musical theatre. Their collaboration led to their first success with Joseph and the "Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat" in 1968, a short cantata initially written for a school production. The piece's popularity grew, and it was eventually expanded into a full-length stage show, becoming a beloved classic.

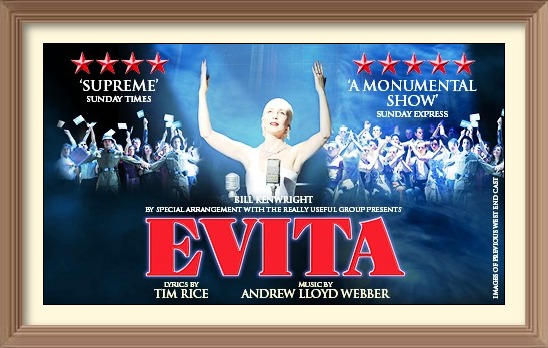

In 1970, Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice created "Jesus Christ Superstar", a rock opera that reimagined the last days of Christ's life through a contemporary lens. Initially released as a concept album, it was soon adapted into a stage production, achieving worldwide acclaim and marking Andrew as a major force in musical theatre. This was followed by "Evita" in 1976, another collaboration with Rice, which chronicled the life of Argentine political leader Eva Perón. The show was both a critical and commercial success, featuring iconic songs like "Don't Cry for Me Argentina."

Lloyd Webber's career continued to flourish with his solo ventures after parting ways with Rice. In 1981, he premiered "Cats", based on T.S. Eliot’s "Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats". The show broke new ground with its unconventional structure and imaginative staging. It became one of the longest-running musicals in history, with notable songs like "Memory" capturing audiences worldwide.

In 1986, Lloyd Webber unveiled "The Phantom of the Opera", a musical inspired by Gaston Leroux's novel. It became his magnum opus, blending soaring melodies, elaborate set designs, and a timeless love story. The production won multiple awards, including the Olivier and Tony Awards for Best Musical, and has remained one of the longest-running and most beloved productions on Broadway and the West End.

Throughout the 1990s and beyond, Lloyd Webber continued to create musicals, including "Aspects of Love", "Sunset Boulevard", "Whistle Down the Wind", and "The Woman in White". Though not all achieved the same level of success as his earlier works, they showcased his versatility and ambition as a composer. He also revisited earlier projects, producing new adaptations and revivals.

In addition to his musical theatre achievements, Lloyd Webber has been a prominent figure in the arts community. He established the Really Useful Group, a production company overseeing his works and other projects. He also became an advocate for arts education and preservation, using his wealth and influence to support music and theatre. In 1992, he was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II for his contributions to music and theatre and was later elevated to the peerage as Baron Lloyd-Webber in 1997.

Andrew Lloyd Webber’s legacy is defined by his ability to craft memorable melodies and his innovative approach to musical theatre. His works have captivated audiences across generations, earning him numerous awards, including multiple Tonys, Grammys, an Oscar, and recognition as one of the most successful composers in history. As a tireless creator, Lloyd Webber continues to influence the world of theatre, ensuring his place in the pantheon of great composers.

The New York Times has referred to him as "the most commercially successful composer in history", The Telegraph ranked him the "fifth most powerful person in British culture", while International Songwriters Association members have consistently voted "Evita" as "the best musical of all time" ahead of such heavyweights as "Singing In The Rain" and "West Side Story".

With all that in mind, any interview with the man himself would have to be approached with some trepidation!

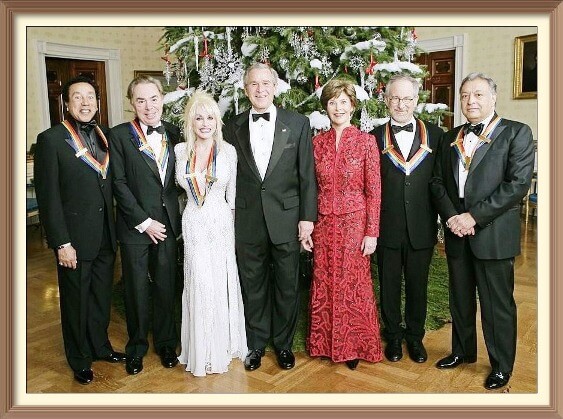

Luckily, we had a legendary author on hand to talk to a star who up to that date, had earned seven Tonys, three Grammys, an Academy Award, fourteen Ivor Novello Awards, seven Olivier Awards, a Golden Globe, a Brit Award, the 2006 Kennedy Center Honours, and the 2008 Classic Brit Award For Outstanding Contribution to Music.

Sheridan Morley, himself a theatre director, as well as being the official biographer of Sir John Gielgud and son of actor Sir Robert Morley, interviewed Sir Andrew Lloyd Webber for the International Songwriters Association's publication "Songwriter Magazine".

When "Jesus Christ Superstar" first opened, it did so on Broadway, something very unusual in your career and I seem to recall you were unhappy at the time.

One of the saddest stories of my life was that, in about 1970, Hal Prince had heard the demo disc we made in London of "Superstar" and he called me asking for the stage rights. But the cable never got to me, and by the time I knew he wanted to direct it, we were in other hands. I often wondered how different my career would have been if Hal had produced my first Broadway show instead of the abortion we finished up with over there.

So why did you open the show on Broadway rather than in London?

Simply because the album had done so much better there; in Britain they said it was a score caught in the crossfire between pop and rock and theatre; and nobody seemed to understand it at first. Tim [Rice] and I were only really known for a very small-scae production of "Joseph", which we had written in 40 minutes for a boys' choir school, and then suddenly there we were being offered a Broadway premiere so, of course, we jumped at it. In the U.S., the album went straight up the charts, and there was a huge feature in Time magazine and there we were. Unfortunately, it was then produced by Tom O'Horgan of "Hair" who didn't really understand what it was about theatrically.

By the time we got the show to London a year or so later, we got it right with a quite different production, directed by Jim Sharman, who had already done it very well in Australia, and we ran for nine years at the Palace on Shaftesbury Avenue, one of the longest-ever runs in West End history.

Even so, it's only now that we are starting again, a quarter of a century later, with another Australian director that I really feel I am going to get the "Superstar" I always wanted, something much more like a musical play than a rock concert. I want the audience to feel they are in an amphitheatre at the time of Christ's trial, and although we have a cast of total unknowns, I think they are a very exciting company. I felt that we shouldn't alter the score, although of course I recognise its faults; it may be naive, but there's a true theatrical through-line.

Meanwhile, another show back from the grave, at it were, "By Jeeves" turns up at Goodspeed in Connecticut this fall. Why bring that back?

Because we did it much too big, with the wrong director and cast, and yet Alan [Ayckbourn] and I had this lingering affection for it. We felt it was somehow unfinished business, and this summer we had a big success with it at Alan's own seaside theatre in Scarborough and now the West End. So when we were offered Goodspeed and the Kennedy Center in Washington in November and December, it seemed worth a try. Then if we can find the right, very small, Broadway house, we plan to take it there in 1997.

Your latest score, 'Whistle Down The Wind," is based on an old Hayley Mills/Alan Bates movie of the 1960s about a group of children at Christmas who mistake an escaped convict for Christ. What led you to that?

Well, I saw a staging of it by the National Youth Music Theatre, which I sponsor in Britain, and I suddenly realised what a wonderful story it was. We've moved the setting to Louisiana, but it is still the tale of children redeeming their elders. Originally, I saw it as a film, but then we did a concert setting of it at my local festival in Sydmonton last summer; and suddenly everyone told me I was mad not to do it for the stage. Hal Prince heard about it and said that, after "Evita" and "Phantom," this was the one he wanted to do next, and you don't turn a man like Prince down. So we opened in Washington with lyrics by Jim Steinman, who, of course, writes all the Meat Loaf material and songs for Bonnie Tyler. We'd long wanted to work together; and this seemed the ideal opportunity.

International Songwriters Association's "Best Musical Of The 20th Century"

Unlike, say, Richard Rodgers, one of the earliest influences on you as a Hollywood musical-struck child, you have worked already with a vast range of lyricists, from Tim Rice through Richard Stilgoe, Don Black, Charles Hart, Alan Ayckbourn and Jim Steinman. Does this suggest that you are a more adaptable composer than is usually suggested?

I think it depends on the individual project; I always construct the original libretto myself; but my problem is that I can't actually put it into the right words. If I could, I suppose I'd be more like Steve Sondheim, at least in working methods. But I can do everything except the lyrics; I plot it all in advance and then look around for the right lyricist..b2One of my own favourite scores - and of all my work, I know it's yours - is "Aspects Of Love" which I would love to see one day as a movie.

But I know the hook and lyrics would need an awful lot more work to get the gossamer effect we would need, the delicacy of say, Steve in "A Little Night Music". Of all the writers I've worked with, I don't think any one would now suit me permanently. It's very rare you find a writer like Hammerstein, who is not only literate but can also write a song which lands; often the younger musical writers now want to do all their own words and all their own music, which tends to cut me out.

Turning to film, why is it only now that Evita has reached the screen, fully 20 years after it first opened on stage?

Firstly, there hasn't been a movie musical which has made money in years and years and years. Secondly, we would never have gotten as far as we are now without the absolute determination of Alan Parker, who made "The Commitments" and "Midnight Express," as well as "Fame" and "Bugsy Malone," which were perhaps the last two examples a decade or more ago of successful film musicals. Once he had fallen in love with "Evita" and cast Madonna and Jonathan Pryce (as Peron) and Antonio Banderas (as Che), we at last had the team.

Alan has always been a very political animal, mixing politics with music in almost all his films, and I have to say the roughcuts I saw were very exciting. The shooting in South America was, however not without its language problems; at one stage, Alan asked for "hundreds of puddles in the road" and finished up to his amazement with 400 yapping poodles all over the set. In the end, they had to shoot a lot of it in Budapest, which looks now just like Buenos Aires in 1950, but "Don't Cry For Me Argentina" is actually sung by Madonna on the balcony of the Casa Rosata in Argentina.

Everybody is going to think I had a lot to do with this film, but in fact the rights were sold decades ago, so my only real involvement was a little extra scoring where it was needed.

Alan Parker himself worked a lot on the script with Tim [Rice]. Early in my career, I wrote the scores for a couple of movies, "Gumshoe" with Albert Finney and "The Odessa File," and, although I didn't enjoy either experience very much and vowed not to do soundtracks again, I was actually very glad that I'd done them when it came to adding the extra music to "Evita". If you are just doing a movie score, you are totally at the mercy of a film you have had nothing else to do with, and somehow that never really appealed to me.

President George W. Bush and Mrs Laura Bush with

William "Smokey" Robinson, Andrew Lloyd Webber,

Dolly Parton, Steven Spielberg and Zubin Mehta

[Photo by Eric Draper, courtesy of The White House]

The inevitable question: will you ever work with Tim Rice again?

It's simply not going to happen, so far as I can see. I don't think at the end of the day he desperately wants me to work with me again, and it's best left at that. I think he now has his own life at Disney with Elton John and Alan Menken, and he seems much happier doing that.

What about the occasional suggestion that you are a control freak?

Odd that, when you think of how many hundreds and maybe thousands of recordings of my songs over which I have no control of any kind once they enter the public domain. I don't think a musical writer ever enjoys anything like the control given to a playwright or a novelist.

Yet talking of just that, you now seem to be spending more and more of your spare time as a journalist, or at any rate a regular food-and-restaurant columnist. What explains that new departure?

Well, I suppose I've always enjoyed writing, that was how I managed to lie my way into Oxford University with some of the worst exam results on record; I just wrote a very good essay, won a place at Magdalen College, and left after a term because there was nothing theatrical going on there and I was bored out of my mind. A few weeks later, back in London, I met Tim, and that was how my whole life started.

I went part-time to the Royal College of Music, but even my father told me it was a waste of time and that they'd educate my music out of me, so I didn't stay there long either. I don't wish to be told how to write a fugue in four parts in the style of Palestrina. Somehow, I don't see that forming queues at a Broadway box office.

In more general terms, how do you see the future of the musical theatre on either side of the Atlantic?

Backstage costs in London, as in New York, have now reached really dangerous levels. I have a feeling that the day of the big musical is ending and that, although "Cats," "Les Mis" and "Phantom" will be with us all over the world for a long time to come, they may well be the first and last of their kind.

"Sunset" and "Saigon" have done their stuff all over the world, but it still is not quite the same as the "big three" and maybe it never will be. I think people have started to look for something a little different in scale, and shows are going to have to get smaller again. "Whistle Down The Wind" and "By Jeeves" are comparatively quite small shows, and I think we've got to rein in our costs.

The technology is now totally out of control. When "West Side Story" first opened, the word "foldback" had never been heard in a theatre; and now if you're not careful you'll get whole casts wearing earpieces. Soon there'll be whole musicals done by robots miming.

What about the belief that the coming of CDs has made audiences unwilling to accept anything but perfect sound in a theatre?

Well, I think it's true that if you and I now heard "Oklahoma" as it was first heard on Broadway in 1943, it might sound pretty ropey to our ears, but I think we've now gone too far the other way and lost the art of careful listening.

Given that, even in Britain, very few radio stations regularly play show tunes nowadays, how do you ever get a hit from the theatre?

Well, Highlights Of Phantom Of The Opera is still No. 4 among Billboard's longest-charting albums, in for 331 weeks and beaten only by "My Fair Lady," Johnny Mathis and Pink Floyd. In that sense, it can still be done. But there's a curious stigma against show music; disc jockeys by and large just don't relate to it. Maybe a show like "Rent" can break through as "Hair" once did. Star singers like Streisand or Minnelli can still take a show song and make it a hit, but by and large the days when even a minor Rodgers-and-Hammerstein score like "Flower Drum Song" would go straight to the top of the charts are long, long gone.

All that changed with the coming of Elvis and the Beatles 30 years ago. Because of Jim Steinman, "Whistle Down The Wind" is the first score of mine that could lift out into the rock charts without much change, so we'll have to see what happens there. Theatre has quite a different imperative, and theatre songs often make no sense at all when heard away from the show.

Also, they tend now to be much longer than most radio stations can stand. We only got "With One Look" from "Sunset Boulevard" to No.30 in the charts even with Streisand singing it. [Streisand's "As If We Never Said Goodbye," from the same show, peaked at No.20.]

To some extent, two of your greatest passions, theatre and architecture, now come together, in that many London and New York theatres are in urgent need of repair and attention.

As indeed are hundreds of our greatest churches. Somehow, we have got to get people to understand that the past has to be paid for just as much as the present.

London this summer had dark theatres just as Broadway always has, and we should have taken the opportunity to get the builders in. Amazingly, there's still a shortage of big musical houses, which is why perhaps in Germany they are now building special theatres for shows of mine and Cameron Mackintosh's, just as they are in Australia. But we are still seeing the five past midnight of the big musical, even as the recession is ending. I believe that, over the next five years, we are going to see some very drastic changes, not only on stage but also backstage, and in terms of real estate.

And finally, having talked of the last 25 years, what of the next for you, personally?

Well, if "Whistle Down The Wind" succeeds, I will at that point have written more musicals than Rodgers and Hammerstein together At that point, I might want to write my art book, but I can't ever see myself leaving the theatre altogether.

Copyright Songwriter Magazine, International Songwriters Association & Sheridan Morley: All Rights Reserved

Postscript

Since 1967, we have spoken with hundreds of songwriters and music publishers, building up a huge collection of detailed interviews which is unmatched anywhere.

Click

HERE to see a list of those currently on this website. And remember, we add new ones every month!

The Main Menu

ISA • International Songwriters Association (1967)

internationalsongwriters@gmail.com

The Small Print

This International Songwriters Association 1967 site is a non-profit non-commercial re-creation of portions of the full site originally published by the International Songwriters Association Limited, and will introduce you to the world of songwriting. It will explain music business terms and help you understand the business concepts that you should be familiar with, thus enabling you to ask more pertinent questions when you meet with your accountant/CPA or solicitor/lawyer.

However, although this website includes general information about legal issues and legal developments as well as accounting issues and accounting developments, it is not meant to be a replacement for professional advice. Such materials are for informational purposes only and may not reflect the most current legal/accounting developments.

Every effort has been made to make this site as complete and as accurate as possible, but no warranty or fitness is implied. The information provided is on an "as is" basis and the author(s) and the publisher shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damages arising from the information contained on this site. No steps should be taken without first seeking competent legal and/or accounting advice

Some pictures on this site are library images supplied by (amongst others) the ISA International Songwriters Association (1967), International Songwriters Association Limited, Dreamstime Library Inc, BMI (Broadcast Music Inc), ASCAP (American Society Of Songwriters, Authors and Publishers), PRS (Performing Rights Society), PPS (Professional Photographic Services), RTE (Radio Telefis Eireann) TV3, and various Public Relations organisations. Other pictures have been supplied by the songwriters, performers, or music business executives interviewed or mentioned throughout this website, while certain pictures are commercial stock footage of businesses and office environments generally, rather than specific images of the ISA, its personnel, facilities or members.

In any event, all images are and remain the property of the individual owners unless indicated to the contrary.

Home •

Interviews •

Writing A Song

|